Current Expenses

The Commonwealth plans to spend $489 billion in 2018-19, and $2,052 billion over the forward estimates. There are indications it may spend more than this, judging by recent announcements on increased GST payments to the States and increased payments related to drought relief.

The breadth of Commonwealth spending is staggering. There is scarcely an area of economic activity to which it does not contribute, either directly or through payments made to the States and local government. There are fifteen major Commonwealth Departments and over 130 Commonwealth agencies which together oversee something like 600 individual spending programs. The Commonwealth makes payments related to new-borns and for bereavement; and, although the young and the old consume most Commonwealth payments, it also pays for a great deal in-between.

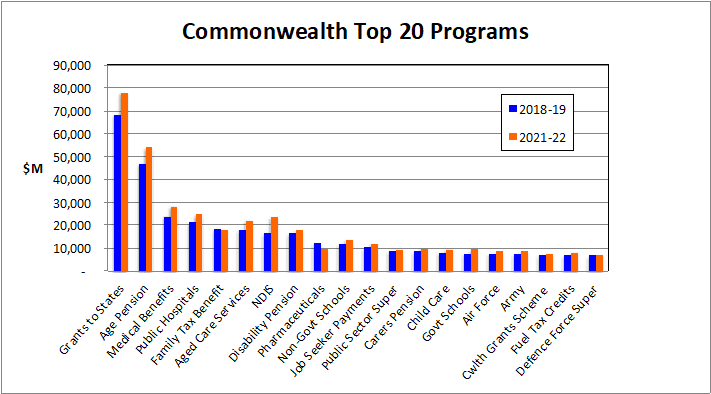

The top 20 programs represent 68% of all expenses - $333 billion. The chart shows the make up of the top 20 expenditure programs as disclosed in the Commonwealth 2018-19 Budget.

Budget Paper No 1 2018-19, Statement 6, Table 3.1, p. 6-10

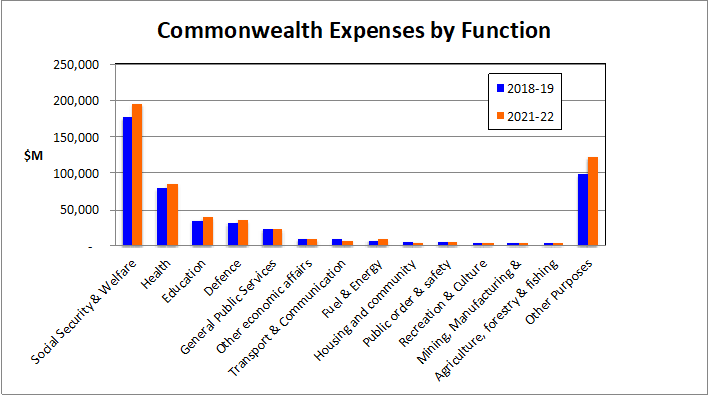

There are other ways of looking at the expense side of the Budget, and one most often used is the functional breakup published in the Budget Papers in Statement 6. This provides a more ‘thematic’ view of expenditure, and allows expenditure to be tracked over time. The following chart provides the breakup, and as above shows both 2018-19 and 2021-22 budgeted expenses.

Budget Paper No 1 2018-19, Statement 6, Table 3, p. 6-7

While “expenses” in this case is almost synonymous with “expenditure”, there is one important exception. Generally speaking the Commonwealth does not own much in the way of physical assets, and the assets it does own – buildings, fit-out, vehicles, IT, etc – are routinely being replaced as they age. So the depreciation included in “expenses” is a reasonable proxy for cash expenditure on assets for most of the Commonwealth, most of the time. The exception is Defence. Defence accounts for 78% of the Commonwealth’s net capital investment in 2018-19, and this figure only increases across the forward estimates – Defence’s net additional capital spending is over $25 billion to 2021-22. Adding net capital investment for Defence to Defence expenses gives a more realistic picture of the demand Defence places on the taxpayer.

Total expenses and net capital investment are driven by policy decisions of Government, as legislated by the Parliament. Policy can be set very specifically, such a decision to provide $x for a specified purpose, or can be set with regard to an entitlement, such as the parameters defining who qualifies for the age pension, and how much they should receive given facts about their individual circumstance.

Most expenditures are relatively self contained – increasing or decreasing expenditure in one area will not automatically affect other expenditures or revenues. Increasing or decreasing the aggregate level of spending however has far more important consequences for the Budget and for the economy. Changes in demand by Government for resources – people, skills, money (i.e. debt) – has impacts on the rest of the economy, and therefore on revenues as well.

More important for most expenditure items are the practical consequences of change, particularly across programs with similar general purposes.

For example:

- Changing the amount of the age pension, or changing eligibility for the age pension, or changing the indexation arrangements would immediately be contrasted with like payments – Veterans pensions and Disability payments. Changing one benefit and not another is fraught with political difficulty.

- Applying the GST to education will dampen demand for private education, and will thereby increase the requirement for the Commonwealth – and more so the States – for spending on public education.

- Changing expenditure for Government schools is very likely to have an impact on the funding required for Non-Government schools.

- Significantly increasing Commonwealth activity, whether that be in Defence, tax collection, border security, or scientific research will require more public servants and more overheads that go with them. Decreasing activity will lessen these costs, but rarely by the same amount and certainly not in the same timeframe.

As with revenue it is important to understand that the expenditure models here take account only of the first round effects of changes you choose to make. A particular problem across many programs which overlap and intersect with State and Territory funding responsibilities such as health, education and roads, is that assumption that the Commonwealth can reduce its contribution without adverse consequences. This is simply not so, however much the overlap of responsibilities contributes to inefficiencies and divided accountability. There is a very good case for clarifying and better delineating Commonwealth, State and local government responsibilities, but that is not achieved by engaging in budgetary pea-and-thimble tricks.